If you received this blog by email, you might

want to visit the actual site. The pictures work much better there.

Just click on the title “Before marriage (equality)….”

Last

week’s US Supreme Court ruling declaring that marriage is a fundamental right

and that barring same-sex couples from access to that right is unconstitutional

unleashed torrents of joy and commentary that have only now, almost two weeks

later, started to ebb. Some folks have bemoaned how long it took us to get to

this point. Personally, I’m astonished at how quickly it happened, especially

relative to other social justice movements. In a single lifetime, my

lifetime—in fact, in what I call my “conscious lifetime,” i.e., the period

since adolescence—the status of LGBT folks has shifted from our being regarded

as illegal, immoral, and insane to our achieving constitutionally sanctioned

participation in what is historically the most revered heterosexual institution

of our society. How amazing to have been present for all of that—and even

engaged in some parts of it.

Just

days after that ruling, we took a long-planned trip to Philadelphia, where we

joined in celebrating the 50th anniversary of the birth of the gay

rights movement. Now, the modern queer rights movement is usually dated from the Stonewall uprising, that iconic moment when

a group of LGBT folks refused to be herded into a police paddy wagon outside a

Mafia-owned bar in NYC. That event, now commemorated around the country by

Pride parades and festivals, happened in the early morning hours of June 28,

1969, some 46 years ago. So why was this celebration on July 4 in Philly—wrong day,

wrong year, wrong city—billed as the 50th anniversary of the LGBT rights

movement?

It's

all about the parts of history we don't usually hear. Here's the story, for

folks who don’t know it, followed by glimpses of this great three-day

celebration.

The

contemporary LGBT movement in the US actually began in the 1950s, though it was known in

those days as the “homophile” movement (the word means, roughly, “affection for

the same”). The primary focus of that movement was on freedom from

discrimination, especially in the workplace, and freedom from police

harassment.

The

event we celebrated in Philadelphia this past week, which preceded Stonewall by

four years, was a carefully coordinated series of pickets (a tactic borrowed

from the African-American Civil Rights movement) carried out by members of this

homophile movement. These gay and lesbian picketers chose Philadelphia because

it’s home to the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution, and perhaps

most importantly, the Liberty Bell. Other folks organizing for their rights—notably,

the abolitionist movement and the suffrage movement—had also employed the

symbolism of that bell. In each case, the argument was that the nation was not

living up to the promise of the founding documents or of the caption inscribed

on the Liberty Bell, “Proclaim Liberty Throughout All the Land

Unto All the Inhabitants thereof.”

|

| Barbara Gittings, a key organizer of the Reminder Days, walking the picket line. |

In

1965, identifying as “homosexual” (the term widely used at the time by LGBT folks

as well as their detractors) could easily land someone in jail or a mental

institution, could mean medical “treatments,” the loss of your job, your

housing, and your relationships with family and friends. Yet in that

atmosphere, 40 brave folks chose to picket in front of Independence Hall in

Philadelphia. The demonstrations began on July 4, 1965, and continued annually

through 1969. The activists called these “Reminder Days”—reminders that a group

of citizens were still excluded from equal rights. The last Reminder Day, which

happened in 1969, just days after the Stonewall uprising, had about 150

picketers. Then, recognizing that Stonewall could be (to quote a speaker from last

week’s event) the Boston Tea Party of the LGBT movement, the organizers turned

their skills to planning the first ever Pride parade in NYC for the year after

Stonewall. And with that commemorative march, the tradition of annual Pride

celebrations and, as legend has it, the contemporary gay rights movement were

born.

It's

not a stretch to say that these daring Reminder Days helped build the momentum

that would launch the modern movement, provided the fuel that Stonewall then

ignited. So why don't we hear more about these folks and their persistent

picketing? Good question, to which I have no definitive answer. But here are

some thoughts.

|

| Frank Kameny, the other main organizer, talks with onlookers |

First,

the early homophile movement has often been criticized as too assimilationist, dismissed

for being so willing to tolerate persistent homophobia, so limited in its aims,

so eager to accept tolerance as an acceptable goal. Some of these early activists

didn't even question the then-dominant notion that homosexuality was a mental

illness—they just thought that this shouldn’t matter as long as the condition

did interfere with a person’s ability to function on the job or in the world.

One indication of their conservative bent was seen in the strict dress code

required of people in the picket lines—men wore suits and ties, women wore

dresses, heels, and pantyhose. The goal was to look “normal” and employable, in

keeping with the aims of that early incarnation of the movement. But from the

perspective of later years and a more ambitious agenda, their stance has been

regarded as regressive at best and drenched in internalized homophobia at

worst.

Which

brings us to a related reason for the relative invisibility of this launching

moment: by 1969, the year of Stonewall, picketing, which was initially regarded

as a radical and risky undertaking, was no longer viewed as radical enough. This was the era when the

student movement, the anti-war movement, the feminist movement, and others were

in full, flowery swing. People were rioting in the streets, taking over campus

buildings, burning draft cards, turning on and dropping out, clashing with

police in hand to hand battle. In the midst of that sort of energy, the Stonewall

rebellion probably looked far more like a happening worthy of consideration as

the origin of this vibrant social change movement than orderly pickets in front

of Constitution Hall ever could be. Interestingly, during the 1969 picket, some

marchers already began violating the dress and behavior codes, wearing more

casual clothing and even holding hands —a clear sign,

if anyone were looking for one, that the movement was morphing. Whatever the

reason, Stonewall quickly became the moment of the movement’s mythical birth, and

the Reminder Days were largely forgotten.

For

the two of us, both LGBT history buffs, this trip was a total treat, a chance

to immerse ourselves for a few days in the events of 1965–1969, a pleasure magnified

by the Supreme Court’s recent marriage ruling. The juxtaposition of our

simultaneous engagement in these half-century-old events and in this

remarkable, singular moment in contemporary history was sort of mind blowing.

What an incredible time to be alive! Imagine it: to have been around at the

time of those early pickets and to still

be around to witness this momentous shift in our place in society. What a gift

to be here, in this movement at this moment.

Our

time in Philly was a three-day submersion in queer history, community, and

celebration—all framed over and over by reminders that we have so much work yet

to do. Marriage was a marvelous accomplishment, but it doesn’t solve enduring

problems of anti-LGBTQ discrimination in housing and employment. It doesn’t

address the pervasive difficulties faced by trans folks, especially trans women

of color. It doesn’t address the needs of LGBTQ youth, especially in poor,

rural, or conservative areas where LGBTQ identity is far from accepted. It

doesn’t address issues related to immigration, doesn’t provide answers to

income equality, doesn’t solve problems of second-parent adoption and other parenting

concerns. Heck, marriage doesn’t even solve the problems of huge numbers of

LGBTQ adults who are, for whatever reason, not joining in that institution.

But

let me stop with the lecture and tell you about our marvelous time in

Philadelphia. First, it felt surprisingly affirming to realize that the city of

Philadelphia was honoring this day as a major historical event. There were 50th

anniversary banners hanging all around the Independence National Historical Park

(the site of Independence Hall, the Constitution Center, Congress Hall, the Liberty

Bell Center, etc.), and the museums that participated had created impressive,

curated exhibits about it. It wasn’t just a token acknowledgement of the date,

but a full-blown city-sponsored occasion. Against this very validating

background, we spent our time dwelling in the historic, the celebratory, and

the challenging.

|

| The "Gay Pioneers" marker with Independence Hall in the background. |

We

began our adventure with a visit to a marker installed by the city of

Philadelphia honoring these so-called Gay Pioneers, where we caught a glimpse

of James Obergefell, the lead plaintiff in the marriage case (and thereby the

benefactor of these early activists’ daring). From there, we moved on to a

packed itinerary of museums, discussions, films, and panels, with meals grabbed

on the run and an inadvertent tour of much of downtown Philadelphia. We heard

panels on legal issues, on legislative issues, on historical perspectives, saw

a film about “Gay Pioneers” and one about Black LGBTQ identities, attended an

interfaith service led by Bishop Gene Robinson at historic Christ Church (where

we sat in the pew that had been reserved for George and Martha Washington and

John Adams), and were treated to lively audience discussions that pointed to

everything from the roots of the LGBT movement in other movements to the sexism

of (even) the queer movement—although that last notion was rejected by the event’s

organizer. Between schedule events, we wandered among sponsoring museums and

institutions—the Museum of African-American History, the Museum of American

Jewish History (which has started a Tumblr site to collect LGBT oral histories),

Liberty Bell Center, and the Museum of We

the People at the National Constitution Center—all of which had major

special exhibits honoring this 50th anniversary.

I

learned so much ... new facts and also new perspectives on things I knew. But

rather than dwell on all that, let me share some of the mood of these excellent

days through a few photos.

|

| Three of the original picketers |

|

| The Liberty Bell Center's silhouette depiction of the Reminder Days (complete with Barbara Gittings' sunglasses) |

|

| The National Museum of American Jewish History offered congratulations outside ... |

|

| ... and exhibits related to Jewish queer experience inside |

|

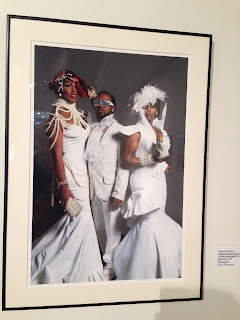

| The African-American History Museum featured Gerard Gaskin's photographic study of the house ballroom culture ... |

|

| ... a celebration of Black and Latino urban queer life that provided a safe space and a support system for queer people of color. |

|

| A pixellated Bishop Gene Robinson led an interfaith service ... |

|

| ... at historic Christ Church, where many "founding fathers" worshiped. |

|

| ... where a break in the rain and some rousing music inspired a bit of flag waving, both queer and patriotic |

All in all, it was a good weekend. A good Reminder.

© Janis

Bohan, 2010-2015. Use of this content is welcome with attribution and a link to

the post.

No comments:

Post a Comment